The Mechanics of the Fastball

It's still the best pitch in baseball and the pitcher's ultimate weapon.

BY JIM KAAT

Published on: May 11, 2004

With a 3-run lead going into the bottom of the eighth in Game 5 of the 2003 American League Championship Series, no one was the least bit surprised when New York Yankees manager Joe Torre called on closer Mariano Rivera to come in and shut down the Boston Red Sox. Rivera, arguably the best closer in the history of baseball, got off to a shaky start, giving up a leadoff triple into the right field corner by Todd Walker and an RBI groundout to Nomar Garciaparra.

The next batter, fearsome slugger Manny Ramirez, had already homered in the game. Another score would bring Boston within one run of the Yankees. It was the classic confrontation--power against power. Ramirez versus Rivera.

But Manny Ramirez had a big advantage. Walking up to the plate, he already knew what Rivera was going to throw him. In fact, all 34,000 fans packed into Fenway Park that night knew what Rivera was going to throw. Essentially, Mariano Rivera throws only one pitch--a hard, heavy cut fastball that breaks slightly to the left just as it crosses the plate. Occasionally, he'll also throw a 98-mph 4-seam fastball that pours straight across the plate, high in the strike zone. That's it.

Ramirez dug in and peered out at Rivera, gearing up for the fastball. Rivera came set and fired. The 4-seamer, 98 miles per hour. Ramirez swung late and missed. Strike one. Rivera had thrown it right by him even though Ramirez knew it was coming. Rivera peered in at catcher Jorge Posada for the sign, came set and fired. The cutter, low and away, 92 miles per hour. Ramirez, way out in front this time, fouled it off. Strike two. You could see Ramirez scowl at Rivera, a determined look on his face. Ramirez would catch up with the next fastball. And it would be a fastball. He knew that. And he would catch up with it.

Rivera peered in, got the sign, came set and delivered. A cutter, high and away. Ramirez, fooled, checked his swing and managed to lay off. Ball one. You could almost hear Ramirez think. The next pitch was going to be a 4-seamer. It had to be.

It was a perfect fastball, textbook perfect. It poured across the plate letter high, 98 miles per hour. Ramirez, simply overmatched even though he had guessed right, swung late and limply. His feeble swing, barely completed as the ball thudded into Posada's mitt, was too little, too late. Mariano Rivera, who went on to take Most Valuable Player honors in the ALCS, had proved it again.

The fastball is still the best pitch in baseball.

Not only is the fastball a deadly weapon in its own right, but it also is the basis for most pitchers' entire game strategies. Everything works off the fastball. Once you establish your fastball in a game, every batter has to be geared up for it since it might come on any given pitch. Once a pitcher has a batter in this overtensed, hair-trigger state, it's much easier to fool him with off-speed and breaking pitches.

But it all starts with the fastball.

A fastball may have been the first pitch thrown in a baseball game, the pitcher attempting to simply overpower the batter. Since that first game in 1845, there have been more variations of the fastball developed than any other pitch. Today, you'll find guys throwing a 2-seam fastball, a 4-seam fastball, a cut fastball, a split-finger fastball and probably others.

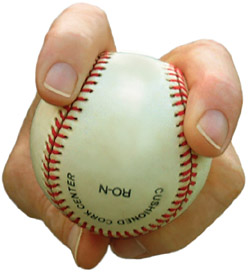

4-Seamer

The 4-seam fastball is the king of the power pitches, and can be delivered with the most accuracy. The grip side view shows how shallow the ball lies in the hand. The ball is held on the wide seams and is thrown over the top. As the ball is released, the fingertips impart straight backspin, with all four seams rotating. This produces a true pitch from the mound to the plate, so there is very little lateral movement.

2-Seamer

The 2-seam fastball is gripped with the fingers on the narrow seams. As with the 4-seamer, you don't want the ball too deep in the hand, a deeper grip effectuating more pull and backspin. Fingertip pressure with either the middle or index finger against the seam generates sidespin, which causes the ball to drop as it nears the plate. This late movement is called a sinking or tailing fastball. Hurled by a lefty, the ball will move down and away from a righthand hitter. Thrown by a righthand pitcher, the ball will move down and away from a lefthand hitter. Whereas the 4-seam fastball is favored by power pitchers, the 2-seamer is used more by ground-ball pitchers.

The Cutter

The cut fastball, or cutter, is thrown using either of the above grips. The key is to keep your hand behind the ball as long as possible and let the grip pressure in the middle finger give it the sidespin or cut. The cutter will move in or out a few inches--like a tight slider--as it nears the plate, but it won't drop like the sinking fastball.

Dry Spitter

The dry spitter is thrown with your fingers on the hide as opposed to the seams of the baseball. Before the spitter was made illegal, hurlers would put saliva on the ball to reduce friction, and it would sort of squirt out of their hand like a pingpong ball. These days, the pitcher can have a little coating of mound dirt on his fingers. This also reduces friction. The ball comes out with virtually no spin and will sink as it reaches the plate.

Split-Finger

The split-finger fastball is released with relatively little spin. The ball has a tumbling rotation and a late downward movement--similar to the dry spitter. You can change the velocity of the split-finger pitch by varying the position and pressure of your fingers on the ball.

The fastball is the only pitch you can throw to all four quadrants of the strike zone, and it's not used nearly enough today. Look at a pitcher's best games, and I'll bet you'll see a high percentage of fastballs and good control. That's why David Wells has been so successful. He favors his fastball, and throws most of them for strikes. His stuff is consistent, start to start, and he has very few arm problems. He trusts his fastball. To be successful, all pitchers, like Wells, need to trust their fastball and say, here it is, hit it if you can!

The Mechanics of the Fastball. PopularMechanics.Com (2005). Retrieved December 4, 2005, from PopularMechanics.com: http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/sports/1283281.html